Most readers today would find his prose style terminally dull, but it always seems to perk up when it comes time to have an attractive heroine kidnapped. Two of his mysteries featuring his detective character Inspector Hanaud have some pretty entertaining and extensive Damsel in Distress scenes: they're lengthy, with more bondage detail than most writers include, and lots of great gloating and character moments.

I suspect he was a villain after my own heart, too, since in both of these stories (and perhaps others for all I know), the central baddie is an evil woman, who is aided by at least one other henchwoman (and, in both cases, an evil maidservant!). He throws in the odd bad guy, too, but compared to the women, they're pretty useless.

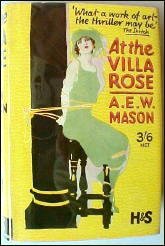

In At The Villa Rose, our heroine, Celia, was once part of a fortune-telling act with her father. When she later finds herself alone and friendless in Paris, she becomes the devoted companion to Mme. Camille Dauvray. The old woman expresses an interest in fortune-telling, and Celia's desire to provide her with a few mystical thrills nearly proves her undoing!

Early in the story, Mason has a character named Ricardo read a newspaper story, laying out a dastardly crime (later, we will revisit the crime, and find out what really happened):

"Late last night," it ran, "an appalling murder was committed at the Villa Rose, on the road to Lac Bourget. Mme. Camille Dauvray, an elderly, rich woman who was well known at Aix, and had occupied the villa every summer for the last few years, was discovered on the floor of her salon, fully dressed and brutally strangled, while upstairs, her maid, Helene Vauquier, was found in bed, chloroformed, with her hands tied securely behind her back. At the time of going to press she had not recovered consciousness, but the doctor, Emile Peytin, is in attendance upon her, and it is hoped that she will be able shortly to throw some light on this dastardly affair. The police are properly reticent as to the details of the crime, but the following statement may be accepted without hesitation:

"The murder was discovered at twelve o'clock at night by the sergent-de-ville Perrichet, to whose intelligence more than a word of praise is due, and it is obvious from the absence of all marks upon the door and windows that the murderer was admitted from within the villa. Meanwhile Mme. Dauvray's motor-car has disappeared, and with it a young Englishwoman who came to Aix with her as her companion. The motive of the crime leaps to the eyes. Mme. Dauvray was famous in Aix for her jewels, which she wore with too little prudence. The condition of the house shows that a careful search was made for them, and they have disappeared. It is anticipated that a description of the young Englishwoman, with a reward for her apprehension, will be issued immediately. And it is not too much to hope that the citizens of Aix, and indeed of Prance, will be cleared of all participation in so cruel and sinister a crime."

Turns out the "young Englishwoman" is someone Ricardo has encountered before:

The Assembly Hall at Leamington, a crowded audience chiefly of ladies, a platform at one end on which a black cabinet stood.

A man, erect and with something of the soldier in his bearing, led forward a girl, pretty and fair-haired, who wore a black velvet dress with a long, sweeping train. She moved like one in a dream.

Some half-dozen people from the audience climbed on to the platform, tied the girl's hands with tape behind her back, and sealed the tape. She was led to the cabinet, and in full view of the audience fastened to a bench. Then the door of the cabinet was closed, the people upon the platform descended into the body of the hall, and the lights were turned very low.

The audience sat in suspense, and then abruptly in the silence and the darkness there came the rattle of a tambourine from the empty platform. Rappings and knockings seemed to flicker round the panels of the hall, and in the place where the door of the cabinet should be there appeared a splash of misty whiteness. The whiteness shaped itself dimly into the figure of a woman, a face dark and Eastern became visible, and a deep voice spoke in a chant of the Nile and Antony. Then the vision faded, the tambourines and cymbals rattled again.

The lights were turned up, the door of the cabinet thrown open, and the girl in the black velvet dress was seen fastened upon the bench within.

It was a spiritualistic performance at which Julius Ricardo had been present two years ago. The young, fair-haired girl in black velvet, the medium, was Celia Harland.

Now, one of the plotters, Helene Vauquier, is telling Inspector Harnaud her version of what happened the night of the murder, with the intention of throwing suspicion on poor Celia.

"I woke up with a feeling of being suffocated. Mon Dieu! There was the light burning in the room, and a woman, the strange woman with the strong hands, was holding me down by the shoulders, while a man with his cap drawn over his eyes and a little black moustache pressed over my lips a pad from which a horribly sweet and sickly taste filled my mouth. Oh, I was terrified! I could not scream. I struggled. The woman told me roughly to keep quiet. But I could not. I must struggle. And then with a brutality unheard of she dragged me up on to my knees while the man kept the pad right over my mouth. The man, with the arm which was free, held me close to him, and she bound my hands with a cord behind me. Look!"

She held out her wrists. They were terribly bruised. Red and angry lines showed where the cord had cut deeply into her flesh.

"Then they flung me down again upon my back, and the next thing I remember is the doctor standing over me and this kind nurse supporting me."

Here, Ricardo, Hanaud, and some guy named Lemerre find Celia, but discover that she's not really the villain(ess) of the piece:

He saw a brightly lit bedroom with a made bed. On his left were the shuttered windows overlooking the lake. On his right in the partition wall a door stood open. Through the door he could see a dark, windowless closet, with a small bed from which the bedclothes hung and trailed upon the floor, as though some one had been but now roughly dragged from it. On a table, close by the door, lay a big green hat with a brown ostrich feather, and a white cloak. But the amazing spectacle which kept him riveted was just in front of him.

An old hag of a woman was sitting in a chair with her back towards them. She was mending with a big needle the holes in an old sack, and while she bent over her work she crooned to herself some French song. Every now and then she raised her eyes, for in front of her, under her charge, Mlle. Celie, the girl of whom Hanaud was in search, lay helpless upon a sofa. The train of her delicate green frock swept the floor. She was dressed as Helene Vauquier had described. Her gloved hands were tightly bound behind her back, her feet were crossed so that she could not have stood, and her ankles were cruelly strapped together. Over her face and eyes a piece of coarse sacking was stretched like a mask, and the ends were roughly sewn together at the back of her head. She lay so still that, but for the labouring of her bosom and a tremor which now and again shook her limbs, the watchers would have thought her dead. She made no struggle of resistance; she lay quiet and still. Once she writhed, but it was with the uneasiness of one in pain, and the moment she stirred the old woman's hand went out to a bright aluminium flask which stood on a little table at her side.

"Keep quiet, little one!" she ordered in a careless, chiding voice, and she rapped with the flask peremptorily upon the table. Immediately, as though the tapping had some strange message of terror for the girl's ear, she stiffened her whole body and lay rigid.

"I am not ready for you yet, little fool," said the old woman, and she bent again to her work.

Ricardo's brain whirled. Here was the girl whom they had come to arrest, who had sprung from the salon with so much activity of youth across the stretch of grass, who had run so quickly and lightly across the pavement into this very house, so that she should not be seen. And now she was lying in her fine and delicate attire a captive, at the mercy of the very people who were her accomplices.

Suddenly a scream rang out in the garden--a shrill, loud scream, close beneath the windows. The old woman sprang to her feet. The girl on the sofa raised her head. The old woman took a step towards the window, and then she swiftly turned towards the door. She saw the men upon the threshold. She uttered a bellow of rage. There is no other word to describe the sound. It was not a human cry; it was the bellow of an angry animal. She reached out her hand towards the flask, but before she could grasp it Hanaud seized her. She burst into a torrent of foul oaths. Hanaud flung her across to Lemerre's officer, who dragged her from the room.

"Quick!" said Hanaud, pointing to the girl, who was now struggling helplessly upon the sofa. "Mlle. Celie!"

Ricardo cut the stitches of the sacking. Hanaud unstrapped her hands and feet. They helped her to sit up. She shook her hands in the air as though they tortured her, and then, in a piteous, whimpering voice, like a child's, she babbled incoherently and whispered prayers. Suddenly the prayers ceased. She sat stiff, with eyes fixed and staring. She was watching Lemerre, and she was watching him fascinated with terror. He was holding in his hand the large, bright aluminium flask. He poured a little of the contents very carefully on to a piece of the sack; and then with an exclamation of anger he turned towards Hanaud. But Hanaud was supporting Celia; and so, as Lemerre turned abruptly towards him with the flask in his hand, he turned abruptly towards Celia too. She wrenched herself from Hanaud's arms, she shrank violently away. Her white face flushed scarlet and grew white again. She screamed loudly, terribly; and after the scream she uttered a strange, weak sigh, and so fell sideways in a swoon. Hanaud caught her as she fell. A light broke over his face.

"Now I understand!" he cried. "Good God! That's horrible."

So now Celia starts to explain stuff for us:

"They came to me a little while ago in that cupboard there--Adele and the old woman Jeanne. They made me get up. They told me they were going to take me away. They brought my clothes and dressed me in everything I wore when I came, so that no single trace of me might be left behind. Then they tied me." She tore off her gloves and showed them her lacerated wrists. "I think they meant to kill me--horribly." And she caught her breath and whimpered like a child. Her spirit was broken.

Inspector Hanaud lays out the fate they had in store for Celia:

"Well, while Adele was preparing her morphia-needle and Hippolyte was about to prepare the boat, Jeanne upstairs was making her preparation too. She was mending a sack. Did you see Mlle. Celie's eyes and face when first she saw that sack? Ah! she understood! They meant to give her a dose of morphia, and, as soon as she became unconscious, they were going perhaps to take some terrible precaution--" Hanaud paused for a second. "I only say perhaps as to that. But certainly they were going to sew her up in that sack, row her well out across the lake, fix a weight to her feet, and drop her quietly overboard. She was to wear everything which she had brought with her to the house. Mlle. Celie would have disappeared for ever, and left not even a ripple upon the water to trace her by!"

OK, now Celia spills all the beans. We learn that she was part of a fortune-telling act as a young girl, but gave it up. Some years later, hungry and broke in Paris, she's befriended by Mme. Dauvray (the old lady who got murdered waaaay back up at the top of the page), and the woman tells Celia of her interest in fortune telling. Celia goes with her to visit a medium, and can easily see through the woman's tricks. In order to satisfy her benefactor's curiosity about such things without being swindled for her money, Celia offers to arrange a seance at the woman's home.

Unfortunately, her friendship with Mme. Dauvray has pushed aside the once-faithful maid Helene Vauquier (who, Mason helpfully informs us, "...was avaricious and greedy, like so many of her class"), angering her at both Celia and MMe. Dauvray. As it happens, Helene is conveniently acquainted with a family of criminals: Adele Tace (who adopts the pseudonym Rossignol), her husband, and her mother Jeanne. With their help, she decides to kill and rob her employer and put the blame on Celia (who, by now, is ashamed of her supposedly harmless deceptions, and wants to end the whole seance business).

Adele makes the acquaintance of Mme. Dauvray, and scoffs at her belief in Celia's seances. She says she'd like to see Celia conduct a seance this way:

"... if, in a word, mademoiselle consents that we tie her hand and foot and fasten her securely in a chair. Such restraints are usual in the experiments of which I have read. Was there not a medium called Mlle. Cook who was secured in this way, and then remarkable things, which I could not believe, were supposed to have happened?"

"Certainly I permit it," said Celia, with indifference; and Mme. Dauvray cried enthusiastically:

"Ah, you shall believe tonight in those wonderful things!"

Adele Tace leaned back. She drew a breath. It was a breath of relief.

"Then we will buy the cord in Aix," she said.

"We have some, no doubt, in the house," said Mme. Dauvray.

Adele shook her head and smiled.

"My dear madame, you are dealing with a sceptic. I should not be content."

Celia shrugged her shoulders.

"Let us satisfy Mme. Rossignol," she said.

Celia, indeed, was not alarmed by this last precaution. She had appeared upon so many platforms, had experienced too often the bungling efforts of spectators called up from the audience, to be in any fear. There were very few knots from which her small hands and supple fingers had not learnt long since to extricate themselves. She was aware how much in all these matters the personal equation counted. Men who might, perhaps, have been able to tie knots from which she could not get free were always too uncomfortable and self-conscious, or too afraid of hurting her white arms and wrists, to do it. Women, on the other hand, who had no compunctions of that kind, did not know how.

Boy, is this girl in for a surprise! The clever Adele even gets Celia to buy her own binding cord!

"Mademoiselle, you can get some cord, I think, at the shop there," and she pointed to the shop of M. Corval. "Madame and I will go slowly on; you, who are the youngest, will easily catch us up." Celia went into the shop, bought the cord, and caught Mme. Dauvray up before she reached the villa.

And now Helene gets in a bit of advance gloating:

Meanwhile, in the hall Helene Vauquier locked and bolted the front door. Then she stood motionless, with a smile upon her face and a heart beating high. All through that afternoon she had been afraid that some accident at the last moment would spoil her plan, that Adele Tace had not learned her lesson, that Celie would take fright, that she would not return. Now all those fears were over. She had her victims safe within the villa. She had them to herself.

Helene arranges things for the seance

The curtains had been loosened at the sides of the arched recess in front of the glass doors, ready to be drawn across. Inside the recess, against one of the pillars which supported the arch, a high stool without a back, taken from the hall, had been placed, and the back legs of the stool had been lashed with cord firmly to the pillar, so that it could not be moved.

Adele looked up at Celia, and laughed maliciously.

"Mademoiselle, I see, is in the very mood to produce the most wonderful phenomena. But it will be better, I think, madame," she said, turning to Mme. Dauvray, "that Mlle. Celie should put on those gloves which I see she has thrown on to a chair. It will be a little more difficult for mademoiselle to loosen these cords, should she wish to do so."

The argument silenced Celia. If she refused this condition now she would excite Mme. Dauvray to a terrible suspicion. She drew on her gloves ruefully and slowly, smoothed them over her elbows, and buttoned them. To free her hands with her fingers and wrists already hampered in gloves would not be so easy a task. But there was no escape.

Adele now gets down to business.

She took up a length of the thin cord.

"Now, how are we to begin?" she said awkwardly. "I think I will ask you, mademoiselle, to put your hands behind you."

Celia turned her back and crossed her wrists. She stood in her satin frock, with her white arms and shoulders bare, her slender throat supporting her small head with its heavy curls, her big hat--a picture of young grace and beauty. She would have had an easy task that night had there been men instead of women to put her to the test. But the women were intent upon their own ends: Mme. Dauvray eager for her seance, Adele Tace and Helene Vauquier for the climax of their plot.

Celia clenched her hands to make the muscles of her wrists rigid to resist the pressure of the cord. Adele quietly unclasped them and placed them palm to palm. And at once Celia became uneasy. It was not merely the action, significant though it was of Adele's alertness to thwart her, which troubled Celia. But she was extraordinarily receptive of impressions, extraordinarily quick to feel, from a touch, some dim sensation of the thought of the one who touched her. So now the touch of Adele's swift, strong, nervous hands caused her a queer, vague shock of discomfort. It was no more than that at the moment, but it was quite definite as that.

"Keep your hands so, please, mademoiselle," said Adele; "your fingers loose."

And the next moment Celia winced and had to bite her lip to prevent a cry. The thin cord was wound twice about her wrists, drawn cruelly tight and then cunningly knotted. For one second Celia was thankful for her gloves; the next, more than ever she regretted that she wore them. It would have been difficult enough for her to free her hands now, even without them. And upon that a worse thing befell her.

"I beg mademoiselle's pardon if I hurt her," said Adele.

And she tied the girl's thumbs and little fingers. To slacken the knots she must have the use of her fingers, even though her gloves made them fumble. Now she had lost the use of them altogether. She began to feel that she was in master-hands. She was sure of it the next instant. For Adele stood up, and, passing a cord round the upper part of her arms, drew her elbows back. To bring any strength to help her in wriggling her hands free she must be able to raise her elbows. With them trussed in the small of her back she was robbed entirely of her strength. And all the time her strange uneasiness grew. She made a movement of revolt, and at once the cord was loosened.

"Mlle. Celie objects to my tests," said Adele, with a laugh, to Mme. Dauvray. "And I do not wonder."

Celia saw upon the old woman's foolish and excited face a look of veritable consternation.

"Are you afraid, Celie?" she asked.

There was anger, there was menace in the voice, but above all these there was fear--fear that her illusions were to tumble about her. Celia heard that note and was quelled by it. This folly of belief, these seances, were the one touch of colour in Mme. Dauvray's life. And it was just that instinctive need of colour which had made her so easy to delude. How strong the need is, how seductive the proposal to supply it, Celia knew well. She knew it from the experience of her life when the Great Fortinbras was at the climax of his fortunes. She had travelled much amongst monotonous, drab towns without character or amusements. She had kept her eyes open. She had seen that it was from the denizens of the dull streets in these towns that the quack religions won their recruits. Mme. Dauvray's life had been a featureless sort of affair until these experiments had come to colour it. Madame Dauvray must at any rate preserve the memory of that colour.

"No," she said boldly; "I am not afraid," and after that she moved no more.

Her elbows were drawn firmly back and tightly bound. She was sure she could not free them. She glanced in despair at Helene Vauquier, and then some glimmer of hope sprang up. For Helene Vauquier gave her a look, a smile of reassurance. It was as if she said, "I will come to your help." Then, to make security still more sure, Adele turned the girl about as unceremoniously as if she had been a doll, and, passing a cord at the back of her arms, drew both ends round in front and knotted them at her waist.

"Now, Celie," said Adele, with a vibration in her voice which Celia had not remarked before.

Excitement was gaining upon her, as upon Mme. Dauvray. Her face was flushed and shiny, her manner peremptory and quick. Celia's uneasiness grew into fear. She could have used the words which Hanaud spoke the next day in that very room--"There is something here which I do not understand." The touch of Adele Tact's hands communicated something to her--something which filled her with a vague alarm. She could not have formulated it if she would; she dared not if she could. She had but to stand and submit.

"Now," said Adele.

She took the girl by the shoulders and set her in a clear space in the middle of the room, her back to the recess, her face to the mirror, where all could see her.

"Now, Celie"--she had dropped the "Mlle." and the ironic suavity of her manner--"try to free yourself."

For a moment the girl's shoulders worked, her hands fluttered. But they remained helplessly bound.

"Ah, you will be content, Adele, to-night," cried Mme. Dauvray eagerly.

But even in the midst of her eagerness--so thoroughly had she been prepared--there lingered a flavour of doubt, of suspicion. In Celia's mind there was still the one desperate resolve.

"I must succeed to-night," she said to herself--"I must!"

Adele Rossignol kneeled on the floor behind her. She gathered in carefully the girl's frock. Then she picked up the long train, wound it tightly round her limbs, pinioning and swathing them in the folds of satin, and secured the folds with a cord about the knees.

She stood up again.

"Can you walk, Celie?" she asked. "Try!"

With Helene Vauquier to support her if she fell, Celia took a tiny shuffling step forward, feeling supremely ridiculous. No one, however, of her audience was inclined to laugh. To Mme. Dauvray the whole business was as serious as the most solemn ceremonial. Adele was intent upon making her knots secure. Helene Vauquier was the well-bred servant who knew her place. It was not for her to laugh at her young mistress, in however ludicrous a situation she might be.

"Now," said Adele, "we will tie mademoiselle's ankles, and then we shall be ready for Mme. de Montespan." [the name of the "spirit" that is to be summoned-- Jeb]

The raillery in her voice had a note of savagery in it now. Celia's vague terror grew. She had a feeling that a beast was waking in the woman, and with it came a growing premonition of failure. Vainly she cried to herself, "I must not fail to-night." But she felt instinctively that there was a stronger personality than her own in that room, taming her, condemning her to failure, influencing the others.

She was placed in a chair. Adele passed a cord round her ankles, and the mere touch of it quickened Celia to a spasm of revolt. Her last little remnant of liberty was being taken from her. She raised herself, or rather would have raised herself. But Helene with gentle hands held her in the chair, and whispered under her breath:

"Have no fear! Madame is watching."

Adele looked fiercely up into the girl's face.

"Keep still, hein, la petite!" she cried. And the epithet--"little one"--was a light to Celia. Till now, upon these occasions, with her black ceremonial dress, her air of aloofness, her vague eyes, and the dignity of her carriage, she had already produced some part of their effect before the seance had begun. She had been wont to sail into the room, distant, mystical. She had her audience already expectant of mysteries, prepared for marvels. Her work was already half done. But now of all that help she was deprived. She was no longer a person aloof, a prophetess, a seer of visions; she was simply a smartly-dressed girl of today, trussed up in a ridiculous and painful position--that was all. The dignity was gone. And the more she realised that, the more she was hindered from influencing her audience, the less able she was to concentrate her mind upon them, to will them to favour her. Mme. Dauvray's suspicions, she was sure, were still awake. She could not quell them. There was a stronger personality than hers at work in the room.

The cord bit through her thin stockings into her ankles. She dared not complain. It was savagely tied. She made no remonstrance. And then Helene Vauquier raised her up from the chair and lifted her easily off the ground. For a moment she held her so. If Celia had felt ridiculous before, she knew that she was ten times more so now. She could see herself as she hung in Helene Vauquier's arms, with her delicate frock ludicrously swathed and swaddled about her legs. But, again, of those who watched her no one smiled.

"We have had no such tests as these," Mme. Dauvray explained, half in fear, half in hope.

Adele Rossignol looked the girl over and nodded her head with satisfaction. She had no animosity towards Celia; she had really no feeling of any kind for her or against her. Fortunately she was unaware at this time that Harry Wethermill had been paying his court to her or it would have gone worse with Mlle. Celie before the night was out. Mlle. Celie was just a pawn in a very dangerous game which she happened to be playing, and she had succeeded in engineering her pawn into the desired condition of helplessness. She was content.

"Mademoiselle," she said, with a smile, "you wish me to believe. You have now your opportunity."

Opportunity! And she was helpless. She knew very well that she could never free herself from these cords without Helene's help. She would fail, miserably and shamefully fail.

"It was madame who wished you to believe," she stammered.

And Adele Rossignol laughed suddenly--a short, loud, harsh laugh, which jarred upon the quiet of the room. It turned Celia's vague alarm into a definite terror. Some magnetic current brought her grave messages of fear. The air about her seemed to tingle with strange menaces. She looked at Adele. Did they emanate from her? And her terror answered her "Yes." She made her mistake in that. The strong personality in the room was not Adele Rossignol, but Helene Vauquier, who held her like a child in her arms. But she was definitely aware of danger, and too late aware of it. She struggled vainly. From her head to her feet she was powerless. She cried out hysterically to her patron:

"Madame! Madame! There is something--a presence here--some one who means harm! I know it!"

And upon the old woman's face there came a look, not of alarm, but of extraordinary relief. The genuine, heartfelt cry restored her confidence in Celia.

"Some one--who means harm!" she whispered, trembling with excitement.

"Ah, mademoiselle is already under control," said Helene, using the jargon which she had learnt from Celia's lips.

Adele Rossignol grinned.

"Yes, la petite is under control," she repeated, with a sneer; and all the elegance of her velvet gown was unable to hide her any longer from Celia's knowledge. Her grin had betrayed her. She was of the dregs. But Helene Vauquier whispered:

"Keep still, mademoiselle. I shall help you."

Helene Vauquier carried the girl into the recess and placed her upon the stool.

With a long cord Adele bound her by the arms and the waist to the pillar, and her ankles she fastened to the rung of the stool, so that they could not touch the ground.

"Thus we shall be sure that when we hear rapping it will be the spirits, and not the heels, which rap," she said. "Yes, I am contented now." And she added, with a smile, "Celie may even have her scarf," and, picking up a white scarf of tulle which Celia had brought down with her, she placed it carelessly round her shoulders.

"Wait!" Helene Vauquier whispered in Celia's ear.

To the cord about Celia's waist Adele was fastening a longer line.

"I shall keep my foot on the other end of this," she said, "when the lights are out, and I shall know then if our little one frees herself."

The three women went out of the recess. And the next moment the heavy silk curtains swung across the opening, leaving Celia in darkness.

Quickly and noiselessly the poor girl began to twist and work her hands. But she only bruised her wrists. This was to be the last of the seances. But it must succeed! So much of Mme. Dauvray's happiness, so much of her own, hung upon its success. Let her fail to-night, she would be surely turned from the door. The story of her trickery and her exposure would run through Aix. And she had not told Harry! It would reach his ears from others. He would never forgive her. To face the old, difficult life of poverty and perhaps starvation again, and again alone, would be hard enough; but to face it with Harry Wethermill's contempt added to its burdens--as the poor girl believed she surely would have to do--no, that would be impossible! Not this time would she turn away from the Seine, because it was so terrible and cold. If she had had the courage to tell him yesterday, he would have forgiven, surely he would!

The tears gathered in her eyes and rolled down her cheeks. What would become of her now? She was in pain besides. The cords about her arms and ankles tortured her. And she feared--yes, desperately she feared the effect of the exposure upon Mme. Dauvray. She had been treated as a daughter; now she was in return to rob Mme. Dauvray of the belief which had become the passion of her life.

"Let us take our seats at the table," she heard Mme. Dauvray say. "Helene, you are by the switch of the electric light. Will you turn it off?" And upon that Helene whispered, yet so that the whisper reached to Celia and awakened hope:

"Wait! I will see what she is doing."

The curtains opened, and Helene Vauquier slipped to the girl's side.

Celia checked her tears. She smiled imploringly, gratefully.

"What shall I do?" asked Helene, in a voice so low that the movement of her mouth rather than the words made the question clear.

Celia raised her head to answer. And then a thing incomprehensible to her happened. As she opened her lips Helene Vauquier swiftly forced a handkerchief in between the girl's teeth, and lifting the scarf from her shoulders wound it tightly twice across her mouth, binding her lips, and made it fast under the brim of her hat behind her head. Celia tried to scream; she could not utter a sound. She stared at Helene with incredulous, horror-stricken eyes. Helene nodded at her with a cruel grin of satisfaction, and Celia realised, though she did not understand, something of the rancour and the hatred which seethed against her in the heart of the woman whom she had supplanted. Helene Vauquier meant to expose her to-night; Celia had not a doubt of it. That was her explanation of Helene Vauquier's treachery; and believing that error, she believed yet another--that she had reached the terrible climax of her troubles. She was only at the beginning of them.

"Helene!" cried Mme. Dauvray sharply. "What are you doing?"

The maid instantly slid back into the room.

"Mademoiselle has not moved," she said.

Celia heard the women settle in their chairs about the table.

"Is madame ready?" asked Helene; and then there was the sound of the snap of a switch. In the salon darkness had come.

If only she had not been wearing her gloves, Celia thought, she might possibly have just been able to free her fingers and her supple hands from their bonds. But as it was she was helpless. She could only sit and wait until the audience in the salon grew tired of waiting and came to her. She closed her eyes, pondering if by any chance she could excuse her failure. But her heart sank within her as she thought of Mme. Rossignol's raillery. No, it was all over for her. ...

She opened her eyes, and she wondered. It seemed to her that there was more light in the recess than there had been when she closed them. Very likely her eyes were growing used to the darkness. Yet--yet--she ought not to be able to distinguish quite so clearly the white pillar opposite to her. She looked towards the glass doors and understood. The wooden shutters outside the doors were not quite closed. They had been carelessly left unbolted. A chink from lintel to floor let in a grey thread of light. Celia heard the women whispering in the salon, and turned her head to catch the words.

"Do you hear any sound?"

"No."

"Was that a hand which touched me?"

"No."

"We must wait."

And so silence came again, and suddenly there was quite a rush of light into the recess. Celia was startled. She turned her head back again towards the window. The wooden door had swung a little more open. There was a wider chink to let the twilight of that starlit darkness through. And as she looked, the chink slowly broadened and broadened, the door swung slowly back on hinges which were strangely silent.

Celia stared at the widening panel of grey light with a vague terror. It was strange that she could hear no whisper of wind in the garden. Why, oh, why was that latticed door opening so noiselessly? Almost she believed that the spirits after all... And suddenly the recess darkened again, and Celia sat with her heart leaping and shivering in her breast. There was something black against the glass doors--a man. He had appeared as silently, as suddenly, as any apparition. He stood blocking out the light, pressing his face against the glass, peering into the room.

For a moment the shock of horror stunned her. Then she tore frantically at the cords. All thought of failure, of exposure, of dismissal had fled from her. The three poor women--that was her thought--were sitting unwarned, unsuspecting, defenceless in the pitch-blackness of the salon. A few feet away a man, a thief, was peering in. They were waiting for strange things to happen in the darkness. Strange and terrible things would happen unless she could free herself, unless she could warn them. And she could not. Her struggles were mere efforts to struggle, futile, a shiver from head to foot, and noiseless as a shiver. Adele Rossignol had done her work well and thoroughly. Celia's arms, her waist, her ankles were pinioned; only the bandage over her mouth seemed to be loosening.

Then upon horror, horror was added. The man touched the glass doors, and they swung silently inwards. They, too, had been carelessly left unbolted. The man stepped without a sound over the sill into the room. And, as he stepped, fear for herself drove out for the moment from Celia's thoughts fear for the three women in the black room. If only he did not see her! She pressed herself against the pillar. He might overlook her, perhaps! His eyes would not be so accustomed to the darkness of the recess as hers. He might pass her unnoticed--if only he did not touch some fold of her dress.

And then, in the midst of her terror, she experienced so great a revulsion from despair to joy that a faintness came upon her, and she almost swooned. She saw who the intruder was. For when he stepped into the recess he turned towards her, and the dim light struck upon him and showed her the contour of his face. It was her lover, Harry Wethermill. Why he had come at this hour, and in this strange way, she did not consider. Now she must attract his eyes, now her fear was lest he should not see her.

But he came at once straight towards her. He stood in front of her, looking into her eyes. But he uttered no cry. He made no movement of surprise. Celia did not understand it. His face was in the shadow now and she could not see it. Of course, he was stunned, amazed. But--but--he stood almost as if he had expected to find her there and just in that helpless attitude. It was absurd, of course, but he seemed to look upon her helplessness as nothing out of the ordinary way. And he raised no hand to set her free.

A chill struck through her. But the next moment he did raise his hand and the blood flowed again, at her heart. Of course, she was in the darkness. He had not seen her plight. Even now he was only beginning to be aware of it. For his hand touched the bandage over her mouth--tentatively. He felt for the knot under the broad brim of her hat at the back of her head. He found it. In a moment she would be free. She kept her head quite still, and then--why was he so long? she asked herself. Oh, it was not possible! But her heart seemed to stop, and she knew that it was not only possible--it was true: he was tightening the scarf, not loosening it. The folds bound her lips more surely. She felt the ends drawn close at the back of her head.

In a frenzy she tried to shake her head free. But he held her face firmly and finished his work. He was wearing gloves, she noticed with horror, just as thieves do. Then his hands slid down her trembling arms and tested the cord about her wrists. There was something horribly deliberate about his movements. Celia, even at that moment, even with him, had the sensation which had possessed her in the salon. It was the personal equation on which she was used to rely. But neither Adele nor this--this STRANGER was considering her as even a human being. She was a pawn in their game, and they used her, careless of her terror, her beauty, her pain.

Then he freed from her waist the long cord which ran beneath the curtain to Adele Rossignol's foot. Celia's first thought was one of relief. He would jerk the cord unwittingly. They would come into the recess and see him. And then the real truth flashed in upon her blindingly. He had jerked the cord, but he had jerked it deliberately. He was already winding it up in a coil as it slid noiselessly across the polished floor beneath the curtains towards him. He had given a signal to Adele Rossignol. All that woman's scepticism and precaution against trickery had been a mere blind, under cover of which she had been able to pack the girl away securely without arousing her suspicions. Helene Vauquier was in the plot, too. The scarf at Celia's mouth was proof of that. As if to add proof to proof, she heard Adele Rossignol speak in answer to the signal.

"Are we all ready? Have you got Mme. Dauvray's left hand, Helene?"

"Yes, madame," answered the maid.

"And I have her right hand. Now give me yours, and thus we are in a circle about the table."

Celia, in her mind, could see them sitting about the round table in the darkness, Mme. Dauvray between the two women, securely held by them. And she herself could not utter a cry--could not move a muscle to help her.

Wethermill crept back on noiseless feet to the window, closed the wooden doors, and slid the bolts into their sockets. Yes, Helene Vauquier was in the plot. The bolts and the hinges would not have worked so smoothly but for her. Darkness again filled the recess instead of the grey twilight. But in a moment a faint breath of wind played upon Celia's forehead, and she knew that the man had parted the curtains and slipped into the room.

Celia let her head fall towards her shoulder. She was sick and faint with terror. Her lover was in this plot--the lover in whom she had felt so much pride, for whose sake she had taken herself so bitterly to task. He was the associate of Adele Rossignol, of Helene Vauquier. He had used her, Celia, as an instrument for his crime. All their hours together at the Villa des Fleurs--here to-night was their culmination. The blood buzzed in her ears and hammered in the veins of her temples. In front of her eyes the darkness whirled, flecked with fire. She would have fallen, but she could not fall. Then, in the silence, a tambourine jangled. There was to be a seance to-night, then, and the seance had begun. In a dreadful suspense she heard Mme. Dauvray speak.

And what she heard made her blood run cold.

Mme Dauvray spoke in a hushed, awestruck voice.

"There is a presence in the room."

It was horrible to Celia that the poor woman was speaking the jargon which she herself had taught to her.

"I will speak to it," said Mme. Dauvray, and raising her voice a little, she asked: "Who are you that come to us from the spirit-world?"

No answer came, but all the while Celia knew that Wethermill was stealing noiselessly across the floor towards that voice which spoke this professional patter with so simple a solemnity.

"Answer!" she said. And the next moment she uttered a little shrill cry--a cry of enthusiasm. "Fingers touch my forehead--now they touch my cheek--now they touch my throat!"

And upon that the voice ceased. But a dry, choking sound was heard, and a horrible scuffling and tapping of feet upon the polished floor, a sound most dreadful. They were murdering her--murdering an old, kind woman silently and methodically in the darkness. The girl strained and twisted against the pillar furiously, like an animal in a trap. But the coils of rope held her; the scarf suffocated her. The scuffling became a spasmodic sound, with intervals between, and then ceased altogether. A voice spoke--a man's voice--Wethermill's. But Celia would never have recognised it--it had so shrill and fearful an intonation.

"That's horrible," he said, and his voice suddenly rose to a scream.

"Hush!" Helene Vauquier whispered sharply. "What's the matter?"

"She fell against me--her whole weight. Oh!"

"You are afraid of her!"

"Yes, yes!" And in the darkness Wethermill's voice came querulously between long breaths. "Yes, NOW I am afraid of her!"

Helene Vauquier replied again contemptuously. She spoke aloud and quite indifferently. Nothing of any importance whatever, one would have gathered, had occurred.

"I will turn on the light," she said. And through the chinks in the curtain the bright light shone. Celia heard a loud rattle upon the table, and then fainter sounds of the same kind. And as a kind of horrible accompaniment there ran the laboured breathing of the man, which broke now and then with a sobbing sound. They were stripping Mme. Dauvray of her pearl necklace, her bracelets, and her rings. Celia had a sudden importunate vision of the old woman's fat, podgy hands loaded with brilliants. A jingle of keys followed.

"That's all," Helene Vauquier said. She might have just turned out the pocket of an old dress.

There was the sound of something heavy and inert falling with a dull crash upon the floor. A woman laughed, and again it was Helene Vauquier.

"Which is the key of the safe?" asked Adele.

And Helene Vauquier replied:--

"That one."

Celia heard some one drop heavily into a chair. It was Wethermill, and he buried his face in his hands. Helene went over to him and laid her hand upon his shoulder and shook him.

"Do you go and get her jewels out of the safe," she said, and she spoke with a rough friendliness.

"You promised you would blindfold the girl," he cried hoarsely.

Helene Vauquier laughed.

"Did I?" she said. "Well, what does it matter?"

"There would have been no need to--" And his voice broke off shudderingly.

"Wouldn't there? And what of us--Adele and me? She knows certainly that we are here. Come, go and get the jewels. The key of the door's on the mantelshelf. While you are away we two will arrange the pretty baby in there."

She pointed to the recess; her voice rang with contempt. Wethermill staggered across the room like a drunkard, and picked up the key in trembling fingers. Celia heard it turn in the lock, and the door bang. Wethermill had gone upstairs.

Celia leaned back, her heart fainting within her. Arrange! It was her turn now. She was to be "arranged." She had no doubt what sinister meaning that innocent word concealed. The dry, choking sound, the horrid scuffling of feet upon the floor, were in her ears. And it had taken so long--so terribly long!

She heard the door open again and shut again. Then steps approached the recess. The curtains were flung back, and the two women stood in front of her--the tall Adele Rossignol with her red hair and her coarse good looks and her sapphire dress, and the hard-featured, sallow maid. The maid was carrying Celia's white coat. They did not mean to murder her, then. They meant to take her away, and even then a spark of hope lit up in the girl's bosom. For even with her illusions crushed she still clung to life with all the passion of her young soul.

The two women stood and looked at her; and then Adele Rossignol burst out laughing. Vauquier approached the girl, and Celia had a moment's hope that she meant to free her altogether, but she only loosed the cords which fixed her to the pillar and the high stool.

"Mademoiselle will pardon me for laughing," said Adele Rossignol politely; "but it was mademoiselle who invited me to try my hand. And really, for so smart a young lady, mademoiselle looks too ridiculous."

She lifted the girl up and carried her back writhing and struggling into the salon. The whole of the pretty room was within view, but in the embrasure of a window something lay dreadfully still and quiet. Celia held her head averted. But it was there, and, though it was there, all the while the women joked and laughed, Adele Rossignol feverishly, Helene Vauquier with a real glee most horrible to see.

"I beg mademoiselle not to listen to what Adele is saying," exclaimed Helene. And she began to ape in a mincing, extravagant fashion the manner of a saleswoman in a shop. "Mademoiselle has never looked so ravishing. This style is the last word of fashion. It is what there is of most chic. Of course, mademoiselle understands that the costume is not intended for playing the piano. Nor, indeed, for the ballroom. It leaps to one's eyes that dancing would be difficult. Nor is it intended for much conversation. It is a costume for a mood of quiet reflection. But I assure mademoiselle that for pretty young ladies who are the favourites of rich old women it is the style most recommended by the criminal classes."

All the woman's bitter rancour against Celia, hidden for months beneath a mask of humility, burst out and ran riot now. She went to Adele Rossignol's help, and they flung the girl face downwards upon the sofa. Her face struck the cushion at one end, her feet the cushion at the other. The breath was struck out of her body. She lay with her bosom heaving.

Helene Vauquier watched her for a moment with a grin, paying herself now for her respectful speeches and attendance.

"Yes, lie quietly and reflect, little fool!" she said savagely. "Were you wise to come here and interfere with Helene Vauquier? Hadn't you better have stayed and danced in your rags at Montmartre? Are the smart frocks and the pretty hats and the good dinners worth the price? Ask yourself these questions, my dainty little friend!"

She drew up a chair to Celia's side, and sat down upon it comfortably.

"I will tell you what we are going to do with you, Mlle. Celie. Adele Rossignol and that kind gentleman, M. Wethermill, are going to take you away with them. You will be glad to go, won't you, dearie? For you love M. Wethermill, don't you? Oh, they won't keep you long enough for you to get tired of them. Do not fear! But you will not come back, Mile. Celie. No; you have seen too much to-night. And every one will think that Mlle. Celie helped to murder and rob her benefactress. They are certain to suspect some one, so why not you, pretty one?"

Celia made no movement. She lay trying to believe that no crime had been committed, that that lifeless body did not lie against the wall. And then she heard in the room above a bed wheeled roughly from its place.

The two women heard it too, and looked at one another.

"He should look in the safe," said Vauquier. "Go and see what he is doing."

And Adele Rossignol ran from the room.

As soon as she was gone Vauquier followed to the door, listened, closed it gently, and came back. She stooped down.

"Mlle. Celie," she said, in a smooth, silky voice, which terrified the girl more than her harsh tones, "there is just one little thing wrong in your appearance, one tiny little piece of bad taste, if mademoiselle will pardon a poor servant the expression. I did not mention it before Adele Rossignol; she is so severe in her criticism, is she not? But since we are alone, I will presume to point out to mademoiselle that those diamond eardrops which I see peeping out under the scarf are a little ostentatious in her present predicament. They are a provocation to thieves. Will mademoiselle permit me to remove them?"

She caught her by the neck and lifted her up. She pushed the lace scarf up at the side of Celia's head. Celia began to struggle furiously, convulsively. She kicked and writhed, and a little tearing sound was heard. One of her shoe-buckles had caught in the thin silk covering of the cushion and slit it. Helene Vauquier let her fall. She felt composedly in her pocket, and drew from it an aluminium flask--the same flask which Lemerre was afterward to snatch up in the bedroom in Geneva. Celia stared at her in dread. She saw the flask flashing in the light. She shrank from it. She wondered what new horror was to grip her. Helene unscrewed the top and laughed pleasantly.

"Mlle. Celie is under control," she said. "We shall have to teach her that it is not polite in young ladies to kick." She pressed Celia down with a hand upon her back, and her voice changed. "Lie still," she commanded savagely. "Do you hear? Do you know what this is, Mlle. Celie?" And she held the flask towards the girl's face. "This is vitriol, my pretty one. Move, and I'll spoil these smooth white shoulders for you. How would you like that?"

Celia shuddered from head to foot, and, burying her face in the cushion, lay trembling. She would have begged for death upon her knees rather than suffer this horror. She felt Vauquier's fingers lingering with a dreadful caressing touch upon her shoulders and about her throat. She was within an ace of the torture, the disfigurement, and she knew it. She could not pray for mercy. She could only lie quite still, as she was bidden, trying to control the shuddering of her limbs and body.

"It would be a good lesson for Mlle. Celie," Helene continued slowly. "I think that if Mlle. Celie will forgive the liberty I ought to inflict it. One little tilt of the flask and the satin of these pretty shoulders--"

She broke off suddenly and listened. Some sound heard outside had given Celia a respite, perhaps more than a respite. Helene set the flask down upon the table. Her avarice had got the better of her hatred. She roughly plucked the earrings out of the girl's ears. She hid them quickly in the bosom of her dress with her eye upon the door. She did not see a drop of blood gather on the lobe of Celia's ear and fall into the cushion on which her face was pressed. She had hardly hidden them away before the door opened and Adele Rossignol burst into the room.

"What is the matter?" asked Vauquier.

"The safe's empty. We have searched the room. We have found nothing," she cried.

"Everything is in the safe," Helene insisted.

"No."

The two women ran out of the room and up the stairs. Celia, lying on the settee, heard all the quiet of the house change to noise and confusion. It was as though a tornado raged in the room overhead. Furniture was tossed about and over the room, feet stamped and ran, locks were smashed in with heavy blows. For many minutes the storm raged. Then it ceased, and she heard the accomplices clattering down the stairs without a thought of the noise they made. They burst into the room. Harry Wethermill was laughing hysterically, like a man off his head. He had been wearing a long dark overcoat when he entered the house; now he carried the coat over his arm. He was in a dinner-jacket, and his black clothes were dusty and disordered.

"It's all for nothing!" he screamed rather than cried. "Nothing but the one necklace and a handful of rings!"

In a frenzy he actually stooped over the dead woman and questioned her.

"Tell us--where did you hide them?" he cried.

"The girl will know," said Helene.

Wethermill rose up and looked wildly at Celia.

"Yes, yes," he said.

He had no scruple, no pity any longer for the girl. There was no gain from the crime unless she spoke. He would have placed his head in the guillotine for nothing. He ran to the writing-table, tore off half a sheet of paper, and brought it over with a pencil to the sofa. He gave them to Vauquier to hold, and drawing out the sofa from the wall slipped in behind. He lifted up Celia with Rossignol's help, and made her sit in the middle of the sofa with her feet upon the ground. He unbound her wrists and fingers, and Vauquier placed the writing-pad and the paper on the girl's knees. Her arms were still pinioned above the elbows; she could not raise her hands high enough to snatch the scarf from her lips. But with the pad held up to her she could write.

"Where did she keep her jewels! Quick! Take the pencil and write," said Wethermill, holding her left wrist.

Vauquier thrust the pencil into her right hand, and awkwardly and slowly her gloved fingers moved across the page.

"I do not know," she wrote; and, with an oath, Wethermill snatched the paper up, tore it into pieces, and threw it down.

"You have got to know," he said, his face purple with passion, and he flung out his arm as though he would dash his fist into her face. But as he stood with his arm poised there came a singular change upon his face.

"Did you hear anything?" he asked in a whisper.

All listened, and all heard in the quiet of the night a faint click, and after an interval they heard it again, and after another but shorter interval yet once more.

"That's the gate," said Wethermill in a whisper of fear, and a pulse of hope stirred within Celia.

He seized her wrists, crushed them together behind her, and swiftly fastened them once more. Adele Rossignol sat down upon the floor, took the girl's feet upon her lap, and quietly wrenched off her shoes.

"The light," cried Wethermill in an agonised voice, and Helena Vauquier flew across the room and turned it off.

All three stood holding their breath, straining their ears in the dark room. On the hard gravel of the drive outside footsteps became faintly audible, and grew louder and came near. Adele whispered to Vauquier:

"Has the girl a lover?"

And Helene Vauquier, even at that moment, laughed quietly.

All Celia's heart and youth rose in revolt against her extremity. If she could only free her lips! The footsteps came round the corner of the house, they sounded on the drive outside the very window of this room. One cry, and she would be saved. She tossed back her head and tried to force the handkerchief out from between her teeth. But Wethermill's hand covered her mouth and held it closed.

The footsteps stopped, a light shone for a moment outside. The very handle of the door was tried. Within a few yards help was there--help and life. Just a frail latticed wooden door stood between her and them. She tried to rise to her feet. Adele Rossignol held her legs firmly. She was powerless. She sat with one desperate hope that, whoever it was who was in the garden, he would break in. Were it even another murderer, he might have more pity than the callous brutes who held her now; he could have no less. But the footsteps moved away. It was the withdrawal of all hope. Celia heard Wethermill behind her draw a long breath of relief. That seemed to Celia almost the cruellest part of the whole tragedy. They waited in the darkness until the faint click of the gate was heard once more. Then the light was turned up again.

"We must go," said Wethermill. All the three of them were shaken. They stood looking at one another, white and trembling. They spoke in whispers. To get out of the room, to have done with the business--that had suddenly become their chief necessity.

Adele picked up the necklace and the rings from the satin-wood table and put them into a pocket-bag which was slung at her waist.

"Hippolyte shall turn these things into money," she said. "He shall set about it to-morrow. We shall have to keep the girl now--until she tells us where the rest is hidden."

"Yes, keep her," said Helene. "We will come over to Geneva in a few days, as soon as we can. We will persuade her to tell." She glanced darkly at the girl. Celia shivered.

"Yes, that's it," said Wethermill. "But don't harm her. She will tell of her own will. You will see. The delay won't hurt now. We can't come back and search for a little while."

He was speaking in a quick, agitated voice. And Adele agreed. The desire to be gone had killed even their fury at the loss of their prize. Some time they would come back, but they would not search now--they were too unnerved.

"Helene," said Wethermill, "get to bed. I'll come up with the chloroform and put you to sleep."

Helene Vauquier hurried upstairs. It was part of her plan that she should be left alone in the villa chloroformed. Thus only could suspicion be averted from herself. She did not shrink from the completion of the plan now. She went, the strange woman, without a tremor to her ordeal. Wethermill took the length of rope which had fixed Celia to the pillar.

"I'll follow," he said, and as he turned he stumbled over the body of Mme. Dauvray. With a shrill cry he kicked it out of his way and crept up the stairs. Adele Rossignol quickly set the room in order. She removed the stool from its position in the recess, and carried it to its place in the hall. She put Celia's shoes upon her feet, loosening the cord from her ankles. Then she looked about the floor and picked up here and there a scrap of cord. In the silence the clock upon the mantelshelf chimed the quarter past eleven. She screwed the stopper on the flask of vitriol very carefully, and put the flask away in her pocket. She went into the kitchen and fetched the key of the garage. She put her hat on her head. She even picked up and drew on her gloves, afraid lest she should leave them behind; and then Wethermill came down again. Adele looked at him inquiringly.

"It is all done," he said, with a nod of the head. "I will bring the car down to the door. Then I'll drive you to Geneva and come back with the car here."

He cautiously opened the latticed door of the window, listened for a moment, and ran silently down the drive. Adele closed the door again, but she did not bolt it. She came back into the room; she looked at Celia, as she lay back upon the settee, with a long glance of indecision. And then, to Celia's surprise--for she had given up all hope--the indecision in her eyes became pity. She suddenly ran across the room and knelt down before Celia. With quick and feverish hands she untied the cord which fastened the train of her skirt about her knees.

At first Celia shrank away, fearing some new cruelty. But Adele's voice came to her ears, speaking--and speaking with remorse.

"I can't endure it!" she whispered. "You are so young--too young to be killed."

The tears were rolling down Celia's cheeks. Her face was pitiful and beseeching.

"Don't look at me like that, for God's sake, child!" Adele went on, and she chafed the girl's ankles for a moment.

"Can you stand?" she asked.

Celia nodded her head gratefully. After all, then, she was not to die. It seemed to her hardly possible. But before she could rise a subdued whirr of machinery penetrated into the room, and the motor-car came slowly to the front of the villa.

"Keep still!" said Adele hurriedly, and she placed herself in front of Celia.

Wethermill opened the wooden door, while Celia's heart raced in her bosom.

"I will go down and open the gate," he whispered. "Are you ready?"

"Yes."

Wethermill disappeared; and this time he left the door open. Adele helped Celia to her feet. For a moment she tottered; then she stood firm.

"Now run!" whispered Adele. "Run, child, for your life!"

Celia did not stop to think whither she should run, or how she should escape from Wethermill's search. She could not ask that her lips and her hands might be freed. She had but a few seconds. She had one thought--to hide herself in the darkness of the garden. Celia fled across the room, sprang wildly over the sill, ran, tripped over her skirt, steadied herself, and was swung off the ground by the arms of Harry Wethermill.

"There we are," he said, with his shrill, wavering laugh. "I opened the gate before." And suddenly Celia hung inert in his arms.

The light went out in the salon. Adele Rossignol, carrying Celia's cloak, stepped out at the side of the window.

"She has fainted," said Wethermill. "Wipe the mould off her shoes and off yours too--carefully. I don't want them to think this car has been out of the garage at all."

Adele stooped and obeyed. Wethermill opened the door of the car and flung Celia into a seat. Adele followed and took her seat opposite the girl. Wethermill stepped carefully again on to the grass, and with the toe of his shoe scraped up and ploughed the impressions which he and Adele Rossignol had made on the ground, leaving those which Celia had made. He came back to the window.

"She has left her footmarks clear enough," he whispered. "There will be no doubt in the morning that she went of her own free will."

Then he took the chauffeur's seat, and the car glided silently down the drive and out by the gate. As soon as it was on the road it stopped. In an instant Adele Rossignol's head was out of the window.

"What is it?" she exclaimed in fear.

Wethermill pointed to the roof. He had left the light burning in Helene Vauquier's room.

"We can't go back now," said Adele in a frantic whisper. "No; it is over. I daren't go back." And Wethermill jammed down the lever. The car sprang forward, and humming steadily over the white road devoured the miles. But they had made their one mistake.

The car had nearly reached Annecy before Celia woke to consciousness. And even then she was dazed. She was only aware that she was in the motor-car and travelling at a great speed. She lay back, drinking in the fresh air. Then she moved, and with the movement came to her recollection and the sense of pain. Her arms and wrists were still bound behind her, and the cords hurt her like hot wires. Her mouth, however, and her feet were free. She started forward, and Adele Rossignol spoke sternly from the seat opposite.

"Keep still. I am holding the flask in my hand. If you scream, if you make a movement to escape, I shall fling the vitriol in your face," she said.

Celia shrank back, shivering.

"I won't! I won't!" she whispered piteously. Her spirit was broken by the horrors of the night's adventure. She lay back and cried quietly in the darkness of the carriage.

The car dashed through Annecy. It seemed incredible to Celia that less than six hours ago she had been dining with Mme. Dauvray and the woman opposite, who was now her jailer. Mme. Dauvray lay dead in the little salon, and she herself--she dared not think what lay in front of her. She was to be persuaded--that was the word--to tell what she did not know. Meanwhile her name would be execrated through Aix as the murderess of the woman who had saved her.

Then suddenly the car stopped. There were lights outside. Celia heard voices. A man was speaking to Wethermill. She started and saw Adele Tace's arm flash upwards. She sank back in terror; and the car rolled on into the darkness. Adele Tace drew a breath of relief. The one point of danger had been passed. They had crossed the Pont de la Caille, they were in Switzerland.

Some long while afterwards the car slackened its speed. By the side of it Celia heard the sound of wheels and of the hooves of a horse. A single-horsed closed landau had been caught up as it jogged along the road. The motor-car stopped; close by the side of it the driver of the landau reined in his horse. Wethermill jumped down from the chauffeur's seat, opened the door of the landau, and then put his head in at the window of the car.

"Are you ready? Be quick!"

Adele turned to Celia.

"Not a word, remember!"

Wethermill flung open the door of the car. Adele took the girl's feet and drew them down to the step of the car. Then she pushed her out. Wethermill caught her in his arms and carried her to the landau. Celia dared not cry out. Her hands were helpless, her face at the mercy of that grim flask. Just ahead of them the lights of Geneva were visible, and from the lights a silver radiance overspread a patch of sky. Wethermill placed her in the landau; Adele sprang in behind her and closed the door. The transfer had taken no more than a few seconds. The landau jogged into Geneva; the motor turned and sped back over the fifty miles of empty road to Aix.

As the motor-car rolled away, courage returned for a moment to Celia. The man--the murderer--had gone. She was alone with Adele Rossignol in a carriage moving no faster than an ordinary trot. Her ankles were free, the gag had been taken from her lips. If only she could free her hands and choose a moment when Adele was off her guard she might open the door and spring out on to the road. She saw Adele draw down the blinds of the carriage, and very carefully, very secretly, Celia began to work her hands behind her. She was an adept; no movement was visible, but, on the other hand, no success was obtained. The knots had been too cunningly tied. And then Mme. Rossignol touched a button at her side in the leather of the carriage.

The touch turned on a tiny lamp in the roof of the carriage, and she raised a warning hand to Celia.

"Now keep very quiet."

Right through the empty streets of Geneva the landau was quietly driven. Adele had peeped from time to time under the blind. There were few people in the streets. Once or twice a sergent-de-ville was seen under the light of a lamp. Celia dared not cry out. Over against her, persistently watching her, Adele Rossignol sat with the open flask clenched in her hand, and from the vitriol Celia shrank with an overwhelming terror. The carriage drove out from the town along the western edge of the lake.

"Now listen," said Adele. "As soon as the landau stops the door of the house opposite to which it stops will open. I shall open the carriage door myself and you will get out. You must stand close by the carriage door until I have got out. I shall hold this flask ready in my hand. As soon as I am out you will run across the pavement into the house. You won't speak or scream."

Adele Rossignol turned out the lamp and ten minutes later the carriage passed down the little street and attracted Mme. Gobin's notice. Marthe Gobin had lit no light in her room. Adele Rossignol peered out of the carriage. She saw the houses in darkness. She could not see the busybody's face watching the landau from a dark window. She cut the cords which fastened the girl's hands. The carriage stopped. She opened the door.

Celia sprang out on to the pavement. She sprang so quickly that Adele Rossignol caught and held the train of her dress. But it was the fear of the vitriol which had made her spring so nimbly. It was that, too, which made her run so lightly and quickly into the house.

The old woman who acted as servant, Jeanne Tace, received her. Celia offered no resistance. The fear of vitriol had made her supple as a glove. Jeanne hurried her down the stairs into the little parlour at the back of the house, where supper was laid, and pushed her into a chair.

Celia let her arms fall forward on the table. She had no hope now. She was friendless and alone in a den of murderers, who meant first to torture, then to kill her. She would be held up to execration as a murderess. No one would know how she had died or what she had suffered. She was in pain, and her throat burned. She buried her face in her arms and sobbed. All her body shook with her sobbing.

Jeanne Rossignol took no notice. She treated Celie just as the others had done. Celia was la petite, against whom she had no animosity, by whom she was not to be touched to any tenderness. La petite had unconsciously played her useful part in their crime. But her use was ended now, and they would deal with her accordingly. She removed the girl's hat and cloak and tossed them aside.

"Now stay quiet until we are ready for you," she said. And Celia, lifting her head, said in a whisper:

"Water!"

The old woman poured some from a jug and held the glass to Celia's lips.

"Thank you," whispered Celia gratefully, and Adele came into the room. She told the story of the night to Jeanne, and afterwards to Hippolyte when he joined them.

"And nothing gained!" cried the older woman furiously. "And we have hardly a five-franc piece in the house."

"Yes, something," said Adele. "A necklace--a good one--some good rings, and bracelets. And we shall find out where the rest is hid--from her." And she nodded at Celia.

The three people ate their supper, and, while they ate it, discussed Celia's fate. She was lying with her head bowed upon her arms at the same table, within a foot of them. But they made no more of her presence than if she had been an old shoe. Only once did one of them speak to her.

"Stop your whimpering," said Hippolyte roughly. "We can hardly hear ourselves talk."

He was for finishing with the business altogether to-night.

"It's a mistake," he said. "There's been a bungle, and the sooner we are rid of it the better. There's a boat at the bottom of the garden."

Celia listened and shuddered. He would have no more compunction over drowning her than he would have had over drowning a blind kitten.

"It's cursed luck," he said. "But we have got the necklace--that's something. That's our share, do you see? The young spark can look for the rest."

But Helene Vauquier's wish prevailed. She was the leader. They would keep the girl until she came to Geneva.

They took her upstairs into the big bedroom overlooking the lake. Adele opened the door of the closet, where a truckle-bed stood, and thrust the girl in.

"This is my room," she said warningly, pointing to the bedroom. "Take care I hear no noise. You might shout yourself hoarse, my pretty one; no one else would hear you. But I should, and afterwards--we should no longer be able to call you 'my pretty one,' eh?"

And with a horrible playfulness she pinched the girl's cheek.

Then with old Jeanne's help she stripped Celia and told her to get into bed.

"I'll give her something to keep her quiet," said Adele, and she fetched her morphia-needle and injected a dose into Celia's arm.

Then they took her clothes away and left her in the darkness. She heard the key turn in the lock, and a moment after the sound of the bedstead being drawn across the doorway. But she heard no more, for almost immediately she fell asleep.

She was awakened some time the next day by the door opening. Old Jeanne Tace brought her in a jug of water and a roll of bread, and locked her up again. And a long time afterwards she brought her another supply. Yet another day had gone, but in that dark cupboard Celia had no means of judging time. In the afternoon the newspaper came out with the announcement that Mme. Dauvray's jewellery had been discovered under the boards. Hippolyte brought in the newspaper, and, cursing their stupidity, they sat down to decide upon Celia's fate. That, however, was soon arranged. They would dress her in everything which she wore when she came, so that no trace of her might be discovered. They would give her another dose of morphia, sew her up in a sack as soon as she was unconscious, row her far out on to the lake, and sink her with a weight attached. They dragged her out from the cupboard, always with the threat of that bright aluminium flask before her eyes. She fell upon her knees, imploring their pity with the tears running down her cheeks; but they sewed the strip of sacking over her face so that she should see nothing of their preparations. They flung her on the sofa, secured her as Hanaud had found her, and, leaving her in the old woman's charge, sent down Adele for her needle and Hippolyte to get ready the boat. As Hippolyte opened the door he saw the launch of the Chef de la Surete glide along the bank.

And, at this point, Hanaud goes on for another chapter or so continuing to explain the story.

Good stuff, eh? And Mason's not done yet.

Back to What's New